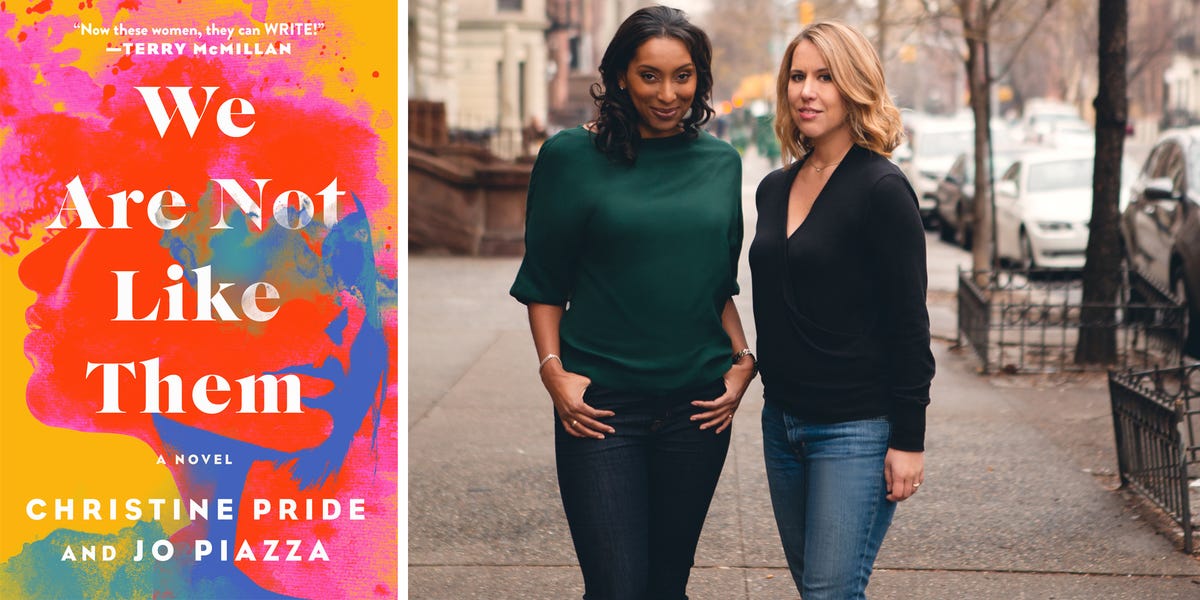

Jo Piazza and Christine Pride first met in 2017, when Pride, a publishing veteran, signed on to edit Piazza’s latest novel, Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win. During the process, the two hit it off and became fast friends, and after completing a second joint project, the novel Marriage Vacation, adapted from Darren Star’s dramedy television series, Younger, they began discussing a co-writing effort that would explore race and police violence through the lens of an interracial friendship like their own.

Releasing October 5, We Are Not Like Them (Atria Books) is told from the alternating perspectives of two childhood friends whose lifelong bond is tested by a tragic incident. Riley Wilson is on her way to becoming one of the first Black female anchors at the top news channel in Philadelphia, while Jen Murphy, who is married to a policeman, is finally pregnant after a series of IVF procedures, the last of which Riley paid for. But when Jen’s husband, Kevin, a white cop, is involved in the shooting of an unarmed Black teenager, each woman must reconcile with the resulting personal implications while figuring out how to come together and chart a path forward as friends.

Over the phone, BAZAAR.com speaks with Piazza and Pride about their decision to tackle such a crucial topic, their prescient co-writing process, and the conversations they hope their book will spark.

What inspired you to write the book, and why was it something you wanted to do as a pair?

Christine Pride: When Jo and I met, I was her editor. We went right from working on Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win to working on Marriage Vacation. Immediately after that, we started talking about the idea of working together on something else. This was in spring of 2018. At the time, there was this rash of police shootings—Stephon Clark, specifically, was killed right around that time. As a book editor, you’re always like, “I’d like to see this kind of book. I like to see this kind of book.” And a book about the police, a friendship, and a relationship between a Black woman and a white woman who are affected by a police shooting was something that felt like a great premise. I mean, a lot to dive into. And so Jo and I started talking about that very loosely.

We realized what an opportunity we had to come together as a Black woman and a white woman to tell this story with our unique perspectives and experiences. We wanted to really raise the stakes for these characters and have a shocking premise for this story, and delve into race and police shootings. This was not something that we were shying away from, but that we were leaning into—but we also wanted to do it in a way that focused on real characters and really dug behind and beyond the headlines with all kinds of nuance and complexity.

Do you remember a specific moment or galvanizing event where you both sat down and decided, let’s do this?

Jo Piazza: No, I don’t, because it was a whirlwind. In the span of three months, we were writing and releasing Marriage Vacation, releasing Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win, and Christine came on book tour with me, which was a road trip through the South in summer of 2018. Being in the South as a Black woman and white woman together, you start to have a lot of conversations about race. At one point, we were at Dollywood—which I still maintain is one of the greatest places in America—we got separated in the parking lot, and Christine ran into a family that was dressed head to toe in Confederate flag clothing. At first, I almost started to laugh it off because it was ridiculous. But then, I had to really absorb what this meant for her as a Black woman in such an all-white space. Being in the car together and having this trip together helped us really start digging into the characters and digging into the conversations that we wanted to have.

Did you know from the start that you wanted it to be told from two different perspectives?

CP: We definitely knew early on that we were going to tell it from two different perspectives back and forth—that was the grounding structure, the nonnegotiable. Everything else grew from there. Our early conversations were definitely about just being creative. Who are these women? Where do they come from? How are they friends? What’s the arc of this story going to be? We did do an outline to start with, which changed along the way. But at least we had a starting point, particularly since we had such a tight structure of back and forth. We chipped away from there in a Google Doc, which was also one of our early decisions. Well, I did not make this decision but—

JP: It was my decision, actually, I was like, “We cannot collaborate in Word. We shall not collaborate in Word!”

CP: I was such a Word girl, Jo dragged me kicking and screaming to Google Docs. But from there, it was a live, dynamic document that we both would go into at 2 a.m. when we couldn’t sleep or—I mean, there was always one of us making changes, comments, suggestions; we were always having a conversation in the comments in Google Doc. Because Jo and I have never lived in the same place at the same time since we met, so much of our relationship was a precursor to the pandemic in terms of everything being online and on Google Hangouts and whatnot.

How would that work? Would you get on a Hangout, talk about what you wanted the next portion of the story to cover, and then one of you would go in, write some of it, and then the other one would go in?

CP: Just like that. It’s funny because a lot of people make the assumption that I wrote the Black characters for Black women and Jo wrote the white characters for white women, which is not true at all. It was a lot of like, “Okay, I wrote that, take a look,” and then the other person would make changes or projections and vice versa.

First and foremost, this is really a story about friendship. What was it like writing about friendship while simultaneously exploring your own?

JP: Yeah. Our friendship has evolved as we’ve been writing this book together. We liked each other a lot when we first started working on Charlotte Walsh, and we had that initial spark where you’re like, “Oh, wait, I think we could be actual friends. Not just like work friends, but actual friends.” All of a sudden, we’re writing a book about both friendship and race at the same time while our own friendship is evolving.

We did have to have the same reckoning about how we talk about race together that our characters have to have on the page. And to be really honest, I hadn’t had those kinds of reckonings. I grew up in a very white town; I went to a white school, it was not diverse. My friend group in college wasn’t diverse. And I didn’t have that many close friends, like your ride-or-dies, of another race until Christine and I became friends.

Meanwhile, Christine has friends of all different races and has been talking about race her entire life. So I came to this friendship not knowing how to have some of these conversations and having to figure it out, which was definitely annoying for Christine. She should not have had to be my professor in how to talk about race 101. We had to figure out how to get past that, and then move forward in both our personal and professional relationships.

Is that something you wanted the book to address: how to talk about race with a friend?

CP: Yeah, absolutely.

JP: We have a lot of goals and missions for this book. We say this statistic a lot: 75 percent of white people in America don’t have a close friend of another race. At its heart, this is about two women that love each other, that are each other’s ride-or-die, and by falling in love with these characters and letting yourself fall in love with the story, you can then maybe come away with new ways to have conversations about race that you might not have been able to have before.

CP: As an editor, it’s been really important to me to make sure that we see different kinds of stories and voices and characters. It was important to us to have Riley be a character we don’t see often enough in books or pop culture in general: a strong, middle-class, driven, ambitious Black woman who comes from a very stable family. In a way, we turn the tropes on their head here with this book, where it’s Jen who struggles more financially and Jen who sees Riley’s family in a savior way, as the kind of family that she wants to have. We’ve just been so immersed in stereotypes about Black people, Black families, Black communities. We wanted to try to make sure that we were showing something different, but also that Riley was just a human, a flawed character. When you see a character like this, it plays against peoples’ unconscious bias in a lot of ways.

You interviewed a lot of different people while writing the book, from policemen to shooting victims. What were those experiences like, and what perspective do they bring to the book?

JP: It was so necessary, because we didn’t want these characters to be one-dimensional. Our goal was to make them all fully formed human beings who are also flawed and real. We interviewed police officers, both men and women. We interviewed a therapist who counsels police officers after officer-involved shootings. We talked to a lot of police wives. Going into this, I didn’t realize how tight-knit of a community and how much of a clique identity being a police wife is. That was fascinating to me.

I was working on a podcast at the same time about gun violence here in Philadelphia, so I was interviewing a lot of shooting victims and the mothers of shooting victims. I can say every single interview that we did informed something that we put in the book or gave us an emotional reference point. We wanted to make sure that no one character was the villain. We wanted to make sure that everything and everyone was painted in shades of gray.

You started writing We Are Not Like Them in 2018, which, of course, was before the killing of George Floyd. Where was the book at that point, and did anything get tweaked in response?

CP: We were actually done with the book, which is just a really fascinating bookend of this journey. And then America just everything turned on a dime, really. There’s one significant change we made to the book, which to some degree involves a spoiler. It has to do with Kevin’s resolution and what happened to him and the circumstances of his involvement. We had done so much research, and the book was really rooted in the reality that indictments, let alone convictions, were at single-digit percentages in cases like this.

We wanted to maintain that the book was set in 2019, but we felt like people were going to want more satisfaction in terms of justice. Really, a question in the book is what is justice? We had to ask ourselves, “What is that going to look like? What is going to be satisfying to readers?” We had the power to change it. We could make art conform in a way that you cannot in real life.

What is your biggest hope for this book?

JP: We’re hoping that it helps readers start conversations that they would have been too nervous to have before, and I mean all kinds of readers. I’m not just talking about white women, because we wrote this book for a very wide audience. We want everyone to see something of themselves in it. And to have conversations starters in it about both friendship and race, and being a woman of a certain age in the world today, which is fucking hard, and we know that.

CP: We also want our book to be a vehicle for people to connect. It’s a hard topic, but we really tried to make the book hopeful too. Or at least filled with a lot of humanity. You can be angry during some pages and sad during some pages and cry at the end then, and maybe even laugh along the way.

Do you have plans to write something together again? Or was this just a very special circumstance?

CP: We are on it! We’re well into our next book, which we’re really excited about. That was always our goal when we started; very early on, we were thinking about how we could build a series or brand around tackling race in intimate spaces. So our first focus is about friendship, but we plan to tackle motherhood and race and workplace and race. So we have lots of ideas, and we are in the midst of—in the Google Doc, very thick in the Google Doc—working away.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Tackling Police Violence Through the Lens of an Interracial Friendship

Source: Filipino Journal Articles

0 Comments